Introduction

One can draw a countless number of parallels between playing fantasy football and investing in the stock market.

You want to buy low and sell high – heading into this offseason, Jaguars RB James Robinson was an ideal sell-high candidate in dynasty leagues.

You want to load up on blue chip assets in the early rounds – tried and true producers like Apple, Microsoft, and Travis Kelce.

You want a diversified portfolio. In dynasty leagues, ideally, you’ll have a good combination of productive assets (value stocks) vs. ascendant assets (growth stocks). And you shouldn’t be too overloaded at one position, or too weak at another.

These are just the most overused and banal examples I could think of, but we could do this all day if we wanted to.

Fundamentally, by investing in the stock market or by playing fantasy football, you’re making a prediction based on how a given asset – a company or a football player – is going to perform in the future. In both cases you can accomplish this by analyzing trends, poring over spreadsheets, and building projections. In both cases, the outcome is largely out of your control. And, actually, according to MIT’s Sports Lab, the outcome is more out of your control (more luck-driven, less skill-driven) in stock market investing than in daily fantasy football (essentially the day-trading equivalent of fantasy football).

Anyway, I’m sure you get the point – fantasy football is a lot like the stock market. But they’re not exactly the same. There’s one interesting way in which they’re diametrically opposed, and that difference will be the focal point of today’s article.

The Major Difference

For years – far too long – I thought there wasn’t any difference between selecting stocks for my portfolio and drafting players for fantasy.

I learned from Warren Buffett that the best investors look for companies with a high margin of safety – what he often referred to as “the three most important words in investing.” Basically, the greater a company’s intrinsic value relative to its cost (market price), the higher the margin of safety, and the better the investment.

I assumed this strategy (prioritize safety) translated perfectly to fantasy football as: “If you draft the best values, you’re going to profit.” This is sort of true, only I was wrong in my assessment of value. The best values aren’t necessarily the players most likely to beat their ADP, or even the players with the greatest disconnect between their fantasy projections and their ADP-based expectation.

With investing, you’re not actually competing against anyone. You’re just trying to maximize the return on your investment. Your upside is limitless. But your downside is horrific – financial ruin. With fantasy football, you’re competing against (typically) nine or 11 other teams. Your upside is a first-place finish. Your downside is (typically) the same as all the other teams – finishing outside of first place. Your chance at turning a profit is roughly around 1 in 12, and your profit margin is capped at something close to 12 times your buy-in. In contrast, the S&P500 has finished in the green in 33 of the past 38 years, and some investors have made billions of dollars in profits. It’s a little more nuanced than this, but clearly downside and risk don’t mean the same thing in investing as they do in fantasy football.

Buffett has been quoted as saying:

“The first rule of investing is ‘Don’t lose money,’ and the second rule is ‘Never forget the first rule.’”

At the heart of investing lies the miracle of compound interest – what Albert Einstein referred to as the eighth wonder of the world. This is what your entire investment strategy should be centered around – maximizing the rate at which you compound capital over time. Once that is understood, it’s easy to see why the best investors are more fearful of loss than they are enticed by gains. Investor and author of The Dao of Capital Mark Spitznagel explains:

“That’s because, you see, it is the big losses that really matter to compounding — more than the small losses, and more than even the big gains for that matter. If you don’t believe me, consider this: Lose 50% one year and it will take almost two +50% years to get you back to even. Steep losses just matter more than anything else… But investors get this wrong, all the time, as they chase the average moment or path.”

With investments, there’s probably a threshold where the downside is significant enough to never outweigh the potential rewards of a given investment. However, in fantasy football, something closer to the opposite is true. Fundamentally, a player’s upside is typically far more valuable than their downside is detrimental, and, at a certain point (in the draft), downside becomes wholly irrelevant.

The 10-Year Treasury Note is an extremely valuable commodity in the world of investing, but in fantasy, similarly low-risk / low-reward investments are rarely worth your time. And a high-risk / high-reward fantasy investment in the 12th round is far more worthwhile than a zero-risk / low-return or even a low-risk / medium-return investment in the same round.

And so, my initial strategy – something along the lines of “draft the players most-likely to beat their ADP” – was flawed, because my assessment of value was wrong. A player merely beating his ADP isn’t enough. This is an extremely common mistake.

We can steal from Spitznagel and repurpose his quote for fantasy as, “Elite scorers just matter more than anything else… But fantasy players get this wrong, all the time, as they chase the average projection or the most likely outcome.”

In fantasy football the importance of the average projection or the most-likely outcome is massively exaggerated. A player’s best-case projection is far more important than their base-case projection, which is more important than their worst-case projection. And in the later rounds, a player’s worst-case projection or their risk is wholly irrelevant. The optimal strategy is to chase upside, and with ADP being more a reflection of a player’s most likely outcome, the optimal strategy also comes at a discount.

Let me explain why.

Power-Law Distributions

Those of you who took Statistics 101 in college may remember learning about the differences between a “normal distribution” and a “power-law distribution.” I never took statistics in college, but I did do the next best thing – namely, read a lot of articles from fantasy football’s preeminent polymath Adam Harstad. And because of that, I feel well-versed on the subject. (And also on the subjects of physics, art history, actuarial science, economics, game theory, etc.) In any case, it’s not so complicated, but Harstad explained these concepts and their fantasy implications better than I could, so allow me to loosely plagiarize two of his older articles (2015, 2017) to better get the point across.

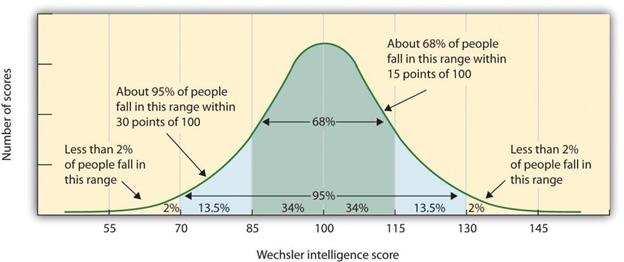

Many things in life follow a “normal distribution” or a “bell curve.” Things like IQ and height follow a normal distribution when plotted on a graph, where the majority of individuals within a population cluster tightly around the average IQ or height. As you can see below, that results in a shape which at least vaguely resembles a bell.

“In a ‘normal distribution’ there is a range of possible outcomes, but most of them pile up around the middle, while outliers become rarer and rarer the further out you go."

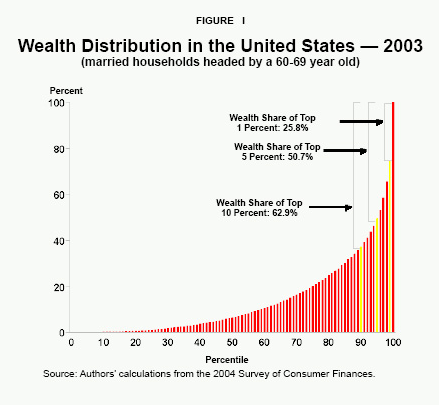

There are some examples of this in fantasy football, but, “the distribution that really rules fantasy is called the ‘power-law distribution,’ which looks more like a ski slope than a bell.” A power-law distribution represents “something highly skewed, with a small number of very high values and a large number of relatively low values."

In the real world, distribution of income tends to follow a power-law distribution. Another example would be Wikipedia — in 2017, Vice found that 77% of Wikipedia is written by just 1% of its contributors.

Harstad’s more apt example was this: "Fantasy performances follow a power-law distribution. If you look, for instance, at the top running back seasons in history (by standard scoring), you will find one season with over 400 points, eight seasons with 350-400 points, 30 seasons with 300-350 points, 110 seasons with 250-300 points, 258 seasons with 200-250 points, 599 seasons with 150-200 points, and 1179 seasons with 100-150 points."

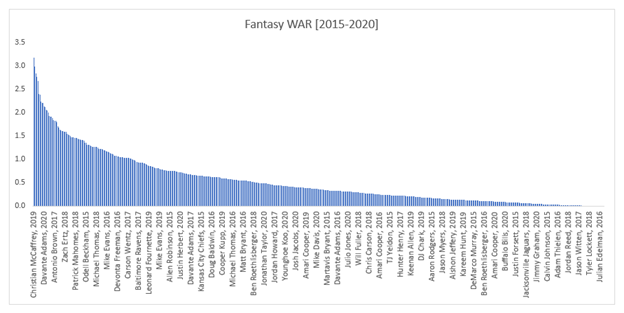

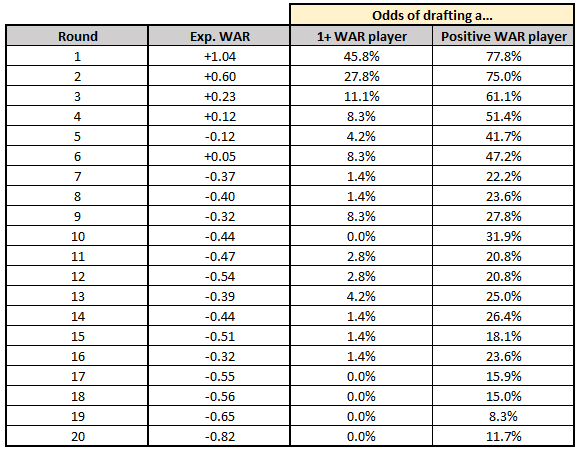

Like fantasy points, fantasy Wins Above Replacement (WAR) also follows this trend. Here are all fantasy starters since 2015:

That datapoint all the way to the left is 2019 Christian McCaffrey, who was worth an astounding 3.2 wins above replacement (WAR) to his fantasy owners. For perspective, that was more than the No. 2 and No. 3 running backs in 2019 combined — Dalvin Cook (1.6) and Aaron Jones (1.3).

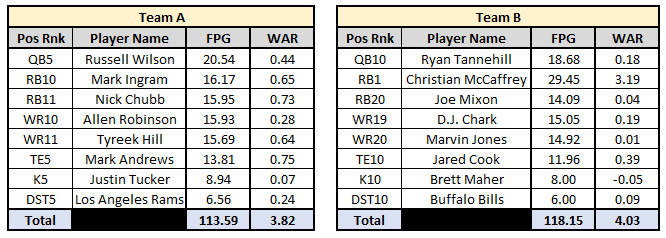

In 2019 PPR leagues, you were better off fielding a team in a 10-team league that consisted of only Christian McCaffrey and the league-worst starter at each position than you were starting a team that consisted of the: QB5, RB10, RB11, WR10, WR11, TE5, K5, and DST5. And that was true by both WAR and fantasy points per game (FPG). (See below.)

Of course, 2019 McCaffrey is an all-time great example, but this is also usually the case with the highest-scoring running back in any given season.

In each of the past six seasons, the overall RB1 and RB24 combined to out-score the RB6 and RB7 by total PPR fantasy points. (By redraft ADP, that's basically trading the 1.07 and the 1.10 for the 1.01 and 6.04 and coming out ahead.) In six of the last seven seasons, the overall WR1 and WR24 combined to out-score the WR7 and WR8.

In any given season, the RB1 isn’t typically just the “most valuable player in fantasy,” but they’re often orders of magnitude more valuable than the next-closest player. And this trend often follows, though less exaggerated, for the RB2 vs. the RB3, the RB3 vs. the RB4, the WR1 vs. the WR2, etc. That’s just the inherent nature of the game.

In most leagues, a team with good players at every position will be less likely to win the league than the team with a few great players surrounded by random waiver adds.

Harstad sums it all up for us:

“For most teams, the root cause of an early exit will probably be attributed to ‘not enough good players.’ That's fine as far as explanations go, but I can provide a better one: ‘not enough great players.’ Because in fantasy football, good players are nice enough to have, but it's the great ones who determine fates. That's the cruel nature of power-law distributions. It's not about consistently getting decisions right. It's about occasionally getting decisions spectacularly right.”

Upside Wins Championships: Examples

In August of 2019, I called Lamar Jackson the “single greatest value in current drafts at any position.” That prediction proved correct: he averaged the most fantasy points per game of any quarterback in any season ever, paying massive dividends on a 12th round ADP. Just by correctly identifying that one breakout player – ignoring whatever else you might have done in the first 11 rounds – you had a 41% chance of making it to your league’s Championship Round.

Then again, Jackson was a sharp pick. If you were sharp enough to draft him, you probably made several other sharp selections elsewhere in your draft. But we can’t say the same thing for Christian McCaffrey, who was sort of just the default No. 2 pick in fantasy drafts.

However, the edge that that No. 2 draft spot and McCaffrey gave you was massive, maybe the biggest of any one player this past decade. Even though McCaffrey drafters probably weren’t as sharp as Jackson drafters, and McCaffrey was 11 rounds more expensive (Jackson’s margin of safety was higher).

McCaffrey was still easily the MVP of the 2019 fantasy season. If you owned McCaffrey, you were essentially a coin flip (48%) to make it to your league’s championship round. And this is what Harstad meant by the cruel nature of power-law distributions. There was no skill involved in drafting McCaffrey — and so it seemed winning your league in 2019 felt predetermined by the cruel or benevolent hand of fate (your randomized draft order).

In 2017, teams who owned Todd Gurley won their championship 34.4% of the time. Just one player, with an ADP inside the top-20, more than tripled your odds of winning your league. And, more impressively, no other player (including waiver wire superstars Alvin Kamara and JuJu Smith-Schuster) posted a win-rate above 25.0%.

These are all examples of the power of the power-law distribution. Leagues were won and lost on these few players, with no one else really coming close to the value they provided. If I can sum it up in a simple bumper-sticker-style phrase it’d be this:

In fantasy football, two nickels are never worth a dime.

But I noticed another interesting trend when tracking player win rates. Every year there’s a number of players who, despite resoundingly beating their ADP, posted below average win rates for their fantasy teams. The example I used last year was James White, who despite beating his ADP and returning starter-worthy production (finishing 19th at an ADP of RB25), returned a win-rate of just 7.7%, well below the league-average rate (10.0%).

Why? Because low-end RB2 production is basically worthless. By WAR, the RB1 in 2019 was 2.0 times as valuable as the RB2, which was 2.2 times as valuable as the RB10, which was 6.5 times as valuable as James White’s 0.11. And this realization should be just as obvious if using a more rudimentary methodology:

Over the past five seasons, the difference between starting the RB20 and the RB35 — a player you can probably find on waivers — has been nothing compared to the difference between starting the RB7 and the RB20 each week (2.8 FPG vs. 5.3 FPG).

And this isn’t just true at the running back position. Low-end starters are fairly worthless at any position.

Broadly speaking, in a typical 12-team 1QB start/sit league, there is basically no difference between:

The QB12 and QB26

The RB20 and the RB35

The WR50 and WR800

The TE6 and TE13

That’s a concept many will struggle with but is generally true.

The difference between QB12 and QB16 levels of production is relatively meaningless. Over the past five seasons, the QB12 has bested the QB16 by just 0.9 FPG. The gap between QB12 and QB26 is far more significant on paper, but only on paper.

And that’s because QB1 production is relatively meaningless if it’s not high-end QB1 production. Why? Because we have a nearly guaranteed floor of mid- to low-end QB1-levels of production just on streaming alone. Sean Koerner cobbled together QB6-levels of production when streaming quarterbacks in 2019 and, in an outlierish year, QB11-levels in 2020. And keep in mind, with this exercise, Koerner was forced to assume you had to add and drop a different quarterback with an ownership percentage below 50% each week. In reality, every year, there’s a number of UDFA QBs who return mid-range QB1-levels of production or better. Koerner was forced to “drop” those quarterbacks with his article, but you could have just added one of the following players and never dropped them.

Last year, Jalen Hurts finished 5th, Justin Herbert finished 8th, and Ryan Tannehill finished 10th in fantasy points per start, all going undrafted in 10-team ESPN leagues. In 2019, we saw Tannehill finish 2nd and Daniel Jones finish 10th with a UDFA ADP. So, because the position is so easily replaceable and you have that guaranteed floor due to streaming, yes, you should absolutely be swinging for the fences when drafting QBs.

The difference between WR50 and WR200 is insignificant because either way you should have better options on your waiver wire.

And that’s a key point. Allow me to use an example.

Quick Detour: Antonio Brown (2020)

Last year I said Antonio Brown was the ultimate “Upside Wins Championships” pick at an ADP of WR79 (Round 18). I owned him in 100% of my FFPC FootballGuysPlayersChampionship and Main Event leagues. And in the Championship Rounds of those leagues (Weeks 15-17), Brown ranked 4th among all WRs in fantasy points, averaging 23.5 FPG.

Even including the opportunity cost of holding him on your bench all year (which admittedly was huge), the results were at least decent in this format. But, I think the process and justification were even better. Here was my reasoning:

What’s Brown’s risk? His downside was the same as all other players, zero points in a worst-case scenario. Of course, facing a suspension, Brown’s chances of scoring zero points were much higher than for many of the players being drafted around him. Even so, his ADP was absolutely stupid. That’s because Antonio Brown’s upside is Antonio Brown. Prior to 2019, Brown had finished fifth, first, first, first, and first at the position in total fantasy points. His upside was almost unrivaled among wide receivers being drafted in the first four rounds, let alone wide receivers around his ADP-range.

Sure, his odds of scoring zero fantasy points were higher than most. But in terms of value to your roster, zero fantasy points also isn’t far off the base case (maybe even best case) scenario of many of the wide receivers being drafted around him. He was barely drafted above (on average) names like Devin Funchess, Steven Sims, Miles Boykin, and Chris Conley. None of these players ever had WR1 or even WR2 upside. And, even if one of them exceeded their ADP-based expectation (let’s say 9.5 FPG, or 63rd at the position last year), that’s still well below starter-worthy production.

In most leagues, zero fantasy points per game for a wide receiver is in no way meaningfully different from a wide receiver averaging 9.5 FPG. Or, fewer fantasy points per game than what Keke Coutee, Christian Kirk, Randall Cobb, and Keelan Cole averaged last year. Were those players winning you any games? In fact, were they ever cracking your starting lineup? Or, were they even rostered? And that’s sort of the point; they weren’t even rostered. We’ll always have the floor and upside of the waiver wire to fall back on. That’s to say, you can always get 9.5 FPG from a Randall Cobb off waivers. But you can also get a potential starter (WR3 or better) like a Robby Anderson, Curtis Samuel, Marvin Jones, or Chase Claypool last year.

And why would you want a Randall Cobb off waivers? You wouldn’t. Points scored on the bench don’t count, and 9.5 fantasy points per game is never cracking your starting lineup. Instead, drop Cobb and swing for the fences again.

UWC: In Practice

Drafting for upside is the recommended approach. But just how much should you prioritize upside? And how can we properly identify the upside of a player ex ante? Well, now things get murky.

1) (League) Size Matters

I’m recommending you prioritize upside and devalue risk when drafting. OK. But what does that mean? How do you actually do that?

The highest upside fathomable for any player is somewhere around Christian McCaffrey’s 2019 season. Very few players — maybe only one player — have that sort of upside. But all players, including McCaffrey have the same downside risk: they score zero points. But a player scoring zero points isn’t much different from a player averaging 1.0, or 2.0, 3.0, or, in most leagues, even 10.0 FPG. Which is to say, any player’s worst-case scenario is merely that they’re droppable; they’re worse than the best available player off waivers.

That floor (best available player off waivers) and, therefore, your risk tolerance is wholly dependent on your league settings. Different leagues have different floors, or a different waiver wire replacement level. The better the floor — the safety net that your waiver wire provides — the more you should be drafting for upside and the less you should be worried about risk.

Embrace the “Upside Wins Championships” ethos, but on a sliding scale in relation to the quality and depth of your waiver wire. The shallower your league — the fewer the teams, the fewer the starting spots, the fewer the bench spots — the more you should be drafting for upside. Because the shallower your league, the better the options available to you on waivers. The better the options, the higher your guaranteed floor and the more opportunities to find a potential every-week starter or a league-winner in-season.

The average replacement player is going to be much better and more valuable in a 10-team ESPN league than a 16-team deep-bench league. Which means your guaranteed floor is much higher. Which means you should be far more focused on upside and not at all worried about downside and risk in a 10-team ESPN league (by far the most popular format in fantasy). But yes, safety and depth will matter and matter significantly more in a 16-team deep-bench league.

Players like James Robinson, Justin Herbert, Logan Thomas, Robert Tonyan, Chase Claypool, Myles Gaskin, Mike Davis, etc. all went undrafted in 10-team ESPN leagues; but all or most were on FFPC Main Event rosters by the start of the season.

On this point, upside matters significantly less in best ball, where, as I showed here, you’re far more likely to win your league by drafting a number of mere ADP-beaters as opposed to the few key power-law players. Because in a best ball league you don’t have the benefit of waivers and free agency serving as your safety net.

But upside might also matter a great deal more in a tournament-style best ball league, or a tournament style start/sit league like the FFPC Main Event where you're competing against up to 2,999 other teams, and 1st place pays out 50X as much as 10th place.

2) The later in the draft, the more you should be chasing upside.

In fantasy football drafts, aim to be a power hitter. It’s more valuable to hit a home run (by drafting a power-law player like Lamar Jackson in 2019) than a bunch of singles or doubles. Remember, in fantasy football, two nickels are never worth a dime.

Okay, sure, but that’s probably not the approach you should be taking in the earliest rounds of the draft.

As we go farther along in the draft the more important upside becomes. Upside maybe isn’t our chief concern in the first round. Derrick Henry and Ezekiel Elliott have about the same upside — it’s sky-high, hence why they’re drafted in the first round. In the fifth round, it matters a great deal more. In the double-digit rounds, upside is just about all that matters. It should be the driving force behind every pick you make.

Looking at fantasy WAR vs. ADP, since 2015, you’d note that from Round 7 on, our WAR-based expectation turns negative. And your odds of drafting a positive WAR player (aka a fantasy starter) is routinely under 30%, with little fluctuation until Round 16 or so. That’s about when my approach shifts — Round 7 in a 12-team league, or Round 8 in a 10-team league — to becoming far more upside-centric.

3) How do we draft for upside?

A player’s best-case projection is more important than their base-case projection, which is more important than their worst-case projection. But how do we create a best-case projection? How can we properly identify players with league-winning upside ex ante?

That’s a good question, and I’m afraid I don’t really have a great answer. I’ve found it’s far more art than science, and far more luck than both. But I wrote these articles to help:

Identifying League-Winners Ex Ante — I wrote this article last year looking at the top 10 league winners over the prior three seasons and showed how in almost every single case I correctly predicted their league-winning upside in the offseason. In the few cases I failed to predict a top-performing season (2017 Todd Gurley), I tried to highlight the important data points (that might have been hinting at league-winning upside) that I mistakenly overlooked.

Anatomy of a League Winner — In this article, I looked at the top league winners over the prior four seasons trying to find common threads tying these players together. And then looked at the players in 2021 who might qualify. I also spent some time discussing which positions were more valuable (and more conducive to producing league-winners) than others and why.

Underrated Upside: Quarterbacks — In this article, I highlight a few key quarterbacks who have league-winning upside in 2021 and who are being severely underrated at current ADP.

Underrated Upside: Running Backs — In this article, I highlight a few key running backs who have league-winning upside in 2021 and who are being severely underrated at current ADP.

Underrated Upside: Wide Receivers — In this article, I highlight a few key wide receivers who have league-winning upside in 2021 and who are being severely underrated at current ADP.

Underrated Upside: Tight Ends— In this article, I highlight a few key tight ends who have league-winning upside in 2021 and who are being severely underrated at current ADP.

As an important aside: be careful not to conflate risk with upside, as many often do. It does not necessarily follow that a higher risk asset offers more upside, though they may often be inversely correlated.

Oh, and, because I had this problem last year… Throughout the entirety of this article I’ve been talking only about season-long upside. Week-to-week upside is fairly irrelevant outside of best ball leagues. In fact it’s often a detriment in comparison to similarly productive players. Which is to say the more volatile and less predictable players will often cause you to start them or sit them in the wrong weeks. And you get diminishing returns on your win expectation after a certain (very high) points threshold is reached (see: Tyler Lockett WAR vs. FPG discrepancy in 2020).

Summary

When it comes to winning fantasy championships, UPSIDE IS EVERYTHING. Our goal when drafting should be trying to identify players with league-winning upside. A player’s bull-case projection matters much more than his base-case projection which matters far more than his bear-case projection. Leagues are won and lost, not by balanced teams drafting a number of good-to-great ADP-beaters, but by teams who correctly identified a few key league-winners and rode those players all the way to a Championship title.

A player’s upside is typically far more valuable than their downside is detrimental, and, at a certain point (in the draft), downside becomes wholly irrelevant.

In fantasy football the importance of the average projection or the most likely outcome is massively exaggerated. A player’s best-case projection is far more important than their base-case projection, which is more important than their worst-case projection. And in the later rounds, a player’s worst-case projection or their risk is wholly irrelevant. The optimal strategy is to chase upside, and with ADP being more a reflection of a player’s most likely outcome, the optimal strategy also comes at a discount.

The distribution that really rules fantasy is called the “power law distribution” whose graph looks more like a ski slope than a bell.

In most leagues, a team with good players at every position will be less likely to win the league than the team with a few great players surrounded by random waiver adds.

In fantasy football, two nickels are never worth a dime.

Broadly speaking, in a typical 12-team 1QB start/sit league, there is very little difference between QB12 vs. QB26, the RB20 vs. RB35, the WR50 vs. WR800, and the TE6 vs. TE13.

In most leagues, zero fantasy points per game for a wide receiver is worth about as much as 9.5 FPG. We’ll always have the floor and upside of the waiver wire to fall back on.

League Size matters. Embrace the “Upside Wins Championships” ethos, but on a sliding scale in relation to the quality and depth of your waiver wire.

The later in the draft, the more you should be chasing upside. In the double-digit rounds, upside is just about all that matters. It should be the driving force behind every pick you make.

Special thanks to Michael Beers, Adam Harstad, FantasyMojo, Mike Sando, and Brian Malone for their help with this article.