Last season Jalen Hurts ranked sixth in fantasy points per start, despite ranking 24th in pass attempts per start and 38th in passer rating.

In 2018, the Ravens named Lamar Jackson their starting quarterback in Week 11. From that point until the end of the season, Jackson ranked eighth among quarterbacks in fantasy points scored despite ranking 25th in pass attempts and 30th in passer rating. Over that same span, fellow rookie Josh Allen ranked third in fantasy points scored despite ranking 21st in pass attempts and 36th in passer rating.

In the previous season, from Week 8 on, Cam Newton ranked second in fantasy points scored, despite ranking 21st in pass attempts and 25th in passer rating.

From 2010-2011, Tim Tebow ranked seventh in fantasy points per start, 42nd in pass attempts per start, and 38th in passer rating.

So, if it wasn’t from passing efficiency or passing volume, where did all of these fantasy points come from?

Across each of these samples, Hurts ranked first, Jackson ranked first, Allen second, Newton first, and Tebow first in rushing attempts per start. As these cherry-picked samples imply, rushing volume is massively important to a quarterback’s fantasy production and upside.

It was once very rare, but much less so now, to find a true dual-threat quarterback starting in the NFL, but the quarterbacks who do qualify tend to be among fantasy’s most productive options. And that’s typically irrespective of their passing volume and efficiency. This is a concept I first became familiar with in 2013, when Rich Hribar informed us that especially mobile quarterbacks are basically a cheat code in fantasy football, known colloquially as the “Konami Code.” It makes sense intuitively as well, with rushing yards being worth 2.5 times as much as passing yards, and rushing touchdowns being worth 1.5 times as much as passing touchdowns.

Re-examining Hribar’s work, by a similar methodology, I can confirm his initial thesis. Since 2000, there have been 41 instances of a quarterback starting in at least 12 games and averaging at least 5.5 rushing attempts per game started in a single season. Among these 41 seasons, those quarterbacks averaged 19.8 fantasy points per game with an average passer rating of only 89.5. For perspective, 19.8 FPG would have ranked directly behind Tom Brady and a passer rating of 89.5 would have ranked directly above Andy Dalton last year.

Remember, average quarterback production has climbed considerably since 2000, so let’s look at it another way. Within our thresholds, of these 41 seasons, we find 34 instances of a quarterback finishing as a QB1 in fantasy points per game (83%), and 24 instances of a quarterback finishing top-six at the position (59%). That’s fairly absurd.

The implication here is that if a quarterback can hit our threshold of 5.5 rushing attempts per game, there’s a good chance that quarterback can put up strong QB1 numbers without having to be even moderately efficient as a passer. Last season, seven different QBs hit that threshold (with a minimum of four games started). That was a new all-time high, and nearly twice as much as the prior 10-year average (3.8 QBs hitting that threshold per season).

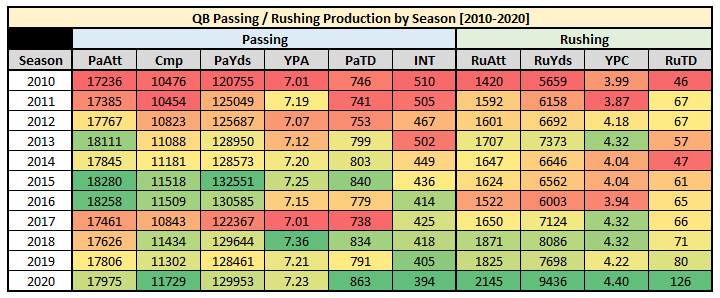

To better illustrate the importance of raw rushing volume for a fantasy quarterback, see the below chart contrasting QB fantasy points scored with rushing attempts in all games since 2000.

I think this chart is fairly straightforward. The more rushing attempts in a game, the more fantasy points scored for a QB. That’s the power of the Konami Code, and the Konami Code has never been more important or more powerful than it is today.

Last season we saw new all-decade highs in rushing attempts, rushing yards, rushing yards per carry, and rushing touchdowns from QBs. And that’s been part of a rising trend for several years now.

Against the prior 10-year average, rushing attempts were up 30%, rushing yards 39%, and rushing touchdowns a whopping 101% in 2020.

Too long didn’t read? The Konami Code is real and it is glorious. And, it’s never been more relevant than it is today.

Tomorrow, we’ll be discussing all of the quarterbacks who might qualify for the Konami Code in 2021, and who you might want to prioritize come draft time.

Addendum

But before we do, I just wanted to make one more important note. While dual-threat ability will often be a massive boon to a QB’s fantasy potential, it can also be a detriment to that QB’s pass-catchers and running backs.

The obvious point is that every rushing attempt for a QB is one less target for a receiver. For instance, last season, Lamar Jackson threw a pass on only 82% of his dropbacks (which, by the way, doesn’t even include his 108 designed runs). For comparison's sake, Ben Roethlisberger attempted a pass on 97% of his dropbacks. So, if they both had 500 dropbacks in a season, Baltimore's receivers would see 75 fewer targets than Pittsburgh’s.

Another more obvious point is the tendency of mobile QBs to vulture touchdowns at the goal line. For instance, last season, Cam Newton scored 11 rushing touchdowns from inside the 10-yard-line, compared to only seven such touchdowns for all New England RBs. And Josh Allen has 25 rushing touchdowns since entering the league, while the next-closest Buffalo RB has only four over the same span (and 18 for the position as a whole). It should be no surprise that Buffalo has ranked bottom-3 in team RB (PPR) fantasy points scored in each of Allen’s three seasons.

Another point, less obvious, is a narrative I’ve often heard but have only now gotten around to testing. And that’s that — even after adjusting for diminished passing volume on the whole — mobile QBs rarely target RBs. And that can be crucial for a RB’s fantasy success. Remember, in PPR leagues, a target is worth 2.73 times as much as a carry. In any case, the argument is that mobile QBs will often pass up a RB serving as a check-down, safety valve, or security blanket and instead elect to run the ball himself. Diving deeper into this narrative, I do think the hypothesis is correct.

Looking at all team seasons over the past decade by QB rush attempts per dropback, there is a clear trend that the more often the QB runs the less often they target their RBs. An average team target share for RBs is somewhere around 19.5%. But, of the top-40 teams (by QB rush attempt per dropback), only seven targeted their RBs 20.0% of the time or more (average target share of 17.6%). In contrast, 20 of the bottom-40 teams hit that threshold, with an average target share of 21.1%.

But, diving deeper, I noticed another interesting trend within these numbers, and another narrative sprung to mind. And that’s that “mobile QBs make things tougher on an opposing defense but easier for their RB when getting touches on the ground.” And that also appears to be the case. Of the top-40 teams (by QB rush attempt per dropback), 20 saw their RBs collectively average 4.5 YPC or more (with an average of 4.39 YPC). Of the bottom-40 teams, only seven saw their RBs average 4.5 YPC or more (with an average of 4.09 YPC).

Joining both narratives together, J.K. Dobbins’ 2020 season starts to make a lot more sense in hindsight. He led the league in YPC (6.0) but averaged just 1.6 targets per game (after averaging 2.0 career targets per game in college). Had he been playing alongside a less mobile QB, I suspect his YPC would have fallen and his target per game average would have risen. The question for Dobbins in 2021 is, and for all RBs playing alongside a Konami Code QB, will the boost in rushing efficiency be enough to offset the occasional goal-line vulturing and the lack of target volume? Personally, I don’t think that it will.